Exegesis

Home > Exegesis > Revelation

Article

Preaching Pictures from Revelation

I expected my sermon series on Revelation to challenge me and my congregation. But I didn't expect that it would also stretch the way I prepared my sermons. It seems fitting now, in hindsight, that such a colorful and evocative text might require a new approach.

My love for the book of Revelation began in Bible College. The professor of my Revelation class would often say "Don't get too caught up in the details. Allow the scene to build in your imagination."

And so, when it came time to preach from Revelation it seemed natural to build a scene in the minds of my listeners. Reading directly from Scripture seemed to encourage them mostly to hear the sound of the words, appealing to a rational part of the mind. Instead, I wanted to preach in a way that appealed to the imagination, like John's visions, evoking images, movement, and emotion.

Drawing a picture

These images are what makes Revelation both so strange and so wonderful—at the same time resisting easy interpretation and drawing us further in. As 21st century readers, with our scientific approach, we can get overwhelmed by the details: dissecting each character and scene to "understand" it. As Craig Keener puts it in the IVP Bible Background Commentary, "As in the Old Testament prophets, much of John's symbolic language is meant as evocative imagery, to elicit particular responses, rather than as a detailed literal picture of events." We're often more comfortable with words like "detailed" and "literal" than with "evocative imagery" and "response."

I never wanted more to be a movie maker than when preparing to preach from Revelation. Because although a 21st century audience brings a scientific approach to Scripture and to sermons, the posture we have in a movie theater is perfect preparation for the Book of Revelation. We go to the movies with open eyes and hearts, allowing the action, characters, and music to take us for a ride. John's scenes of multitudes and martyrs, beasts and thrones require a similar openness, a similar whole-hearted, child-like engagement.

Since I've never been to film school, I did the next best thing: I decided that instead of reading the visions, I would describe them in my own words. I'll never forget my preparation for the sermon on Revelation 12, my favorite scene. There were so many details to remember! The pregnant woman is clothed with the sun and has the moon under her feet (or is she clothed with the moon and has the sun under her feet?) How many stars are in her crown? And the dragon who threatens to eat her child has seven heads and ten horns or is it ten heads and seven horns? But the woman and her child are saved and where do they go again?

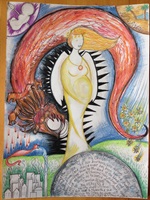

So to help myself remember I drew a detailed sketch with all the details and suddenly the work of remembering became fun. (In fact, my then twelve year-old son, who happens to love dragons, had some opinions on how the dragon should look and went to get his blackest black pen to ink over the horns I'd drawn which just weren't scary enough.) By the time I'd colored all the stars in her crown I couldn't forget there were seven. But even beyond that, when the image was done I'd spent several hours in the scene, experiencing anxiety as the drooling dragon sat in anticipation over its prey, sensing the immensity of the tail that could wipe stars from the sky, feeling the deep relief when the child was whisked away to God and his throne. That experience allowed me not only to see but to feel the scene.

Prompting imagination

And so I began the sermon not with the usual reading of the text but with a telling of it. I invited listeners to just let the words wash over them, let the emotions come. I encouraged them to go to that mental space we visit when we read a novel and allow the scene to play out in our imaginations. I reminded them (as my professor had) not to get caught up too much in any one detail, but to allow the scene to grow and that we'd "look" at it together when it was ready. I invited them to close their eyes if it helped. And then I took a deep breath and began:

"Imagine with me a woman …"

And as I spoke, the scene from my illustration built in my own mind and my words painted images that hovered in the space just over the congregation. I wish I could have seen the various ways it took shape in each imagination—the ways it took on peculiar characteristics of each personality in the room and the ways we might have found each other's scenes strangely familiar, like watching various movie adaptations of a favorite book.

Once we had created the vision together—my words prompting their imaginings—we could pause the action and "walk" among the characters together. Now I could ask questions of the scene—Who represents goodness and evil? What do we expect will happen when an immense dragon preys upon a woman in labor? Who do we expect will win? Who do we expect to be defeated? What is surprising?

I was then able to relate the story to our own lives. In what ways do we feel a ravenous dragon is poised over us? How are we sure we're overcome? In what ways do we feel vulnerable like the woman or baby? Do we trust that our God promises victory? How can this story help us remember we're not overcome even if we feel we are? How will believing we are not overcome help us be hopeful and courageous? How will knowing we will not be overcome by evil keep us from falling into evil?

Images and emotions

Although I preached this sermon several years ago I still hear folks refer to the vision from Revelation because they now hold the images and emotions of it in their own minds. I trust that, just as God uses passages whose words we've memorized, bringing them to mind for future lessons and encouragements, he might also use those pictures. I hope that when someone is feeling overwhelmed by oppressive forces, God might bring to mind that vision of the dragon that doesn't win.

Every week, as preachers, we take so much care to connect with the hearts and minds and imaginations of our folks. And yet, as much as we invest in the effort, we can never really know if or how that connection happens. We have to believe that although we are plying our craft as preachers, the ultimate artist at work here is the Spirit, drawing together text and voice and ears and heart and life.

After I preached this message, and during a following Sunday, I got to see the Spirit's artistry in a very tangible way when Violet, an eight-year-old in the congregation shared with me the picture she drew while she listened to my sermon.

As you can see, it's not unlike the picture I drew. And then I knew St. John, Violet, and I had all seen the same dragon. And, I trust, felt the same courage.

Mandy Smith is the pastor of St Lucia Uniting Church in Brisbane, Australia, and author of The Vulnerable Pastor: How Human Limitations Empower Our Ministry and Unfettered: Imagining a Childlike Faith Beyond the Baggage of Western Culture. Her latest book, Confessions of an Amateur Saint: The Christian Leader's Journey from Self-Sufficiency to Reliance on God, releases in October 2024. Mandy teaches for The Eugene Peterson Center for Christian Imagination and Fuller Seminary. Learn more at www.TheWayIsTheWay.org.