Skill Builders

Article

Illustrate Like Max Lucado and John Ortberg

In When God Whispers Your Name, Max Lucado writes:

I rolled out of bed early—real early. I'd been on vacation for a couple of weeks, and I was rested. My energy level was high, so I dressed to go to the church office. My wife, Denalyn, tried to convince me not to go.

"It's the middle of the night," she mumbled. "What if a burglar tries to break in?"

There had been an attempted break-in at the office a few weeks previously. [Ignoring my wife's concern, I drove to the church,] entered the office complex, disarmed the alarm, and then re-armed it.

A few seconds later the sirens screamed. Somebody is trying to break in! I raced down the hall, turned off the alarm, ran back to my office, and dialed 911. After I hung up, it occurred to me that the thieves could get in before the police arrived. I dashed back down the hall and re-armed the system.

"They won't get me," I mumbled defiantly as I punched in the code.

As I turned, the sirens blared again. I disarmed the alarm and reset it. I walked to a window to look for the police. The alarm sounded a third time. Once again I disarmed it and reset it.

Walking back to my office, the alarm sounded again. I disarmed it. Wait a minute; this alarm system must be fouled up. I called the alarm company.

"Our alarm system keeps going off," I told the fellow who answered. "We've either got some determined thieves or a malfunction."

"There could be one other option," he said. "Did you know that your building is equipped with a motion detector?"

Then the police arrived. "I think the problem is on the inside, not the outside," I told them, embarrassed that I was the culprit setting of the alarm.

Am I the only one to blame an inside problem on an outside source?

Alarms sound in your world as well. Heaven knows you don't silence life's alarm by pretending they aren't screaming. But heaven also knows it's wise to look in the mirror before you peek out the window.

Take in a book or sermon by Max Lucado or John Ortberg, and it's hard not to envy. Somehow they transform the daily experiences we all have into illustrations that are not only inspiring and delightful, but also pregnant with spiritual truth.

Obviously John and Max have enormous God-given talent, but that talent includes skills any preacher can develop. Here are seven core skills for turning the experiences of daily life into illustrations that illumine Scriptural truth.

Continual Searching

John Ortberg refers to the habit of continually searching for illustrations as always having his antennae up. We search all the channels of daily life. Once we develop the habit, it's second nature; our instincts sense an illustration automatically.

To develop this habit, begin a discipline of pausing every 30 minutes to scan that period. The search may last 30 seconds. Search the internal world of what you have been thinking and feeling (strong feelings nearly always signal illustration potential). Search the external, physical world for potential metaphors. Search people's interactions.

Don't concern yourself immediately with whether or not your find illustrates something; just notice what is interesting. If nothing stands out, identify the human situation: a first-time mother struggling to care for a newborn, a worker racing to get to the office on time, a leader under attack. Such ordinary situations often supply the brief illustrative bridges we use to introduce the relevance of a Scripture. If nothing else presents itself, simply scan sensory data: the sound of a fellow worker's footsteps, the smell of old furniture, the lingering taste of breakfast.

The last step in developing the habit of observation is recording what you find. Keep a hard-copy journal nearby, or have a Word file open on your computer all day as a log where you briefly jot the fruit of your sifting every 30 minutes. Write just a phrase and a few topic words. One of my recent entries was: "Utilities worker scans the sidewalk for gas line with a scope. Discernment, vision, test, secrets."

The Pyramid of Abstraction

The second fundamental skill for illustrating like Max and John is the ability to work intentionally with the pyramid of abstraction. With this simple yet powerful model, we can turn virtually any experience into an illustration.

Here's how it works. In the figure below, notice how the words proceed from bottom to top in a movement from specific and concrete to general and abstract. Each step up the inverted pyramid is a broader category.

We can run the same sort of progression with our daily experiences to find illustration topics.

For example, I was sitting recently at the park on a summer day enjoying a few hours off. Nearby, several robins were hunting for a midday meal. I paused to really observe. As I did, it struck me that these innocent-looking birds, which symbolize the beauty of nature and the return of spring, are in reality vicious killers. They hop along in the grass, pause cutely, cock their heads, and stare at the ground. Then they pounce on their unsuspecting prey, savagely pounding their beaks like jackhammers into the soil, sending dirt flying until they seize the unarmed father or mother of many baby worms and mercilessly snip it into pieces. With a slurp, the robins gobble up their still-writhing victims. But their bloodlust is not satisfied. They are serial killers. Without remorse, they hop off to repeat their brutality.

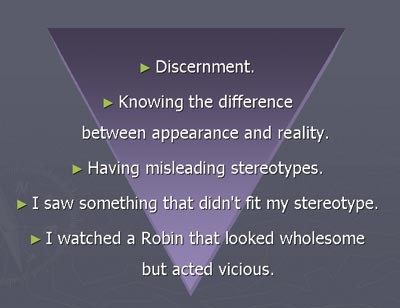

What does this scene illustrate? How does this red-breasted Rambo line up on the pyramid of abstraction? I would begin by brainstorming possible subjects: finding food, eating, hunting, surprises, killing, provision, appearances, false impressions, assumptions, cruelty, daily food, daily needs. Then I would begin low on the pyramid with specific, concrete subjects. I would move up the pyramid filling in words already brainstormed and adding others as they came to mind, proceeding to ever broader generalities until I found a subject that had relevance for preaching.

Once we reach a level of abstraction that has relevance for preaching, we often will want to reverse direction and press down again for concrete specifics in that parallel area.

If I told this story in a sermon about God's provision, I could bridge from it in this way: "Have you ever felt as though you had to be a little heartless, or selfish, to make a living?"

Most of our daily experiences can yield several different lines of thought on the pyramid. Here is another angle on the robin, this time focused on my perceptions.

In a message on spiritual discernment, I could tell the robin story and then bridge in this way: "Things are not always what they seem … ."

As these examples show, most experiences can illustrate something if we try different angles and go high enough on the pyramid. Though I don't actually write on a pyramid when I think about illustrations, I do intentionally think about moving between what is specific and what is general, and am aware that several steps can be involved as I move in one direction or the other.

Keywords

When we observe an interesting daily life experience and begin to brainstorm possible illustration topics or fiddle with the pyramid of abstraction, some people will have a greater capacity to generate ideas than others. What determines that capacity is knowledge.

Finding ways to turn the brief and mundane into the substantial and interesting will chisel your storytelling muscles.

Let me illustrate. As a boy, I received a clear-plastic coin-sorter one Christmas—the kind meant for kids, not bank clerks. You could watch the coins roll down a winding path and then drop through slots of varying sizes that sorted them into piles of pennies, nickels, dimes, and quarters. The sequence of these variable-sized slots mattered, proceeding from smallest to largest. If the largest slot, intended for quarters, had been first, all the coins would have fallen in the quarters pile. But with the smallest slot, intended for dimes, being first, the larger coins would roll over it and proceed down the steep path until they came to a slot large enough for them to drop. When the slots discriminate in this manner between various coins, gravity does the rest.

In the world of illustrations, the discriminating slots are concepts, which all have words. Redemption, mercy, generosity, law, prayer, adultery. You can illustrate only what you understand—what you have a concept, a category, a word for. This is why good illustrators are people who know the concepts of the Bible, of theology, of life and literature.

And so the better we understand theology, the more readily we will recognize that an experience fits the category of atonement or holiness. The better we know the Bible, the more readily an experience will call to mind a Bible verse or story such as the greed of Achan. The more we read life and literature, the more readily an experience will trigger concepts like loss or longing or frustration. If your knowledge is limited to quarter-sized concepts like love, God, or faith, then you will miss the chance to find that perfect illustration for a more specific, dime-sized concept like brotherly love, God's grace, or childlike faith.

We need real knowledge. As someone has said, if you cannot illustrate an idea, you don't really understand it. If you cannot take an abstraction at the top of the pyramid and press down to a concrete example at the bottom point of the inverted pyramid, you don't get it. Somehow the path must be established between top and bottom. Once you have the ability to press down the pyramid from general abstractions to concrete specifics, then the way opens for reverse traffic. … Hmmm, perhaps it's the other way around: Does the journey move from the bottom up? Or is it pressed from both directions? Whichever, the more frequent the traffic on the road, the broader the road becomes, and the quicker connections are made.

At the practical level, then, the more we (a) illustrate abstract ideas and (b) assign abstract words to concrete experiences, the better becomes the illustration highway. Illustrating is an ability that grows with use.

For (b) above—the practice of assigning words—the keywords list of PreachingToday.com can be a valuable resource for you. To aid in your search, we divided the list into three layers of categories for accessing the concepts you need. See the area in PreachingToday.com for browsing by master topics: http://www.preachingtoday.com/illustrations/browse.html.

Telling a Story

Like columns in government buildings, story is the natural form for illustration. If we can't tell a decent story, we will be seriously handicapped. Fortunately, many have written in recent decades on how to tell stories well, and great examples abound. I especially recommend the section on storytelling in The Art and Craft of Biblical Preaching (Zondervan, 2005). 1 In addition, since most of a preacher's stories are true, you will benefit from reading a book on how to tell nonfiction stories using fictional techniques (such as dialogue, sensory details, scenes). I recommend Jon Franklin's Writing for Story (Plume, 1986). 2

In addition to reading on the subject, the best way to learn to tell stories is to tell them every day. At one of your daily meals with family or friends, tell a story based on one of your best illustrations from the last 24 hours (see point one, Continual Searching).

Very important: many of these slices of life will not feel like stories because they have little or no plot, but tell them anyway. As you maintain this habit, you will learn to accentuate a spare plot with rich description. You will learn to create suspense and build to a climax. You will feel the benefits that come with using dialogue and thought-monologues. You will look for the irony and humor in the situation. You will discover how to elicit sympathy or antipathy for the people in the accounts. Finding ways to turn the brief and mundane into the substantial and interesting will chisel your storytelling muscles.

This dinner-table storytelling of everyday, common occurrences is an especially good training ground for sermon illustrating because a good portion of sermon illustrations are likewise spare stories limited in plot, action, and suspense. They are bridges to a preaching point. They only set the stage with a phrase, image, or concept.

Here is a spare story typical in sermons:

I was on my way over to Wheaton College the other day, and, as I stopped at the light at Geneva road, I started watching a wrecking crew tear down the banquet hall on the corner. A bulldozer with jaws designed to munch a building in pieces was ripping away at the roof. Workers were spraying water to keep down the dust and separating bricks from pieces of steel. Half the building was already gone. One of the things not yet demolished, though, was the tall sign out front, which struck me as odd because the marquee still had an old message posted. It said something like "Congratulations Tim and Becky!" Later, I noticed that the sign, with its message, stayed up for several weeks after the building was completely gone. The message outlived the institution.

Although this illustration has little plot, I developed other elements that gave it the feel of a story. I painted a scene through visual description. There is a sense of time passing as my eyes take in the scene and then I say what I saw weeks later. And I built to a climax by holding till the end the detail about the sign and its message.

In contrast, the non-story form of this illustration might sound like this: "I saw an interesting sight the other day: a half-demolished restaurant, with the sign out front still standing. What struck me as funny was the message on the sign had not yet been removed. The message outlived the institution."

Clearly, stories are more interesting.

Figurative and Literal

The potential for illustrating from daily experiences expands greatly when we remember that we can use slices of life literally, figuratively, or both. Figurative use involves metaphor, simile, symbol, analogy; one thing resembles or represents another. By contrast, in literal use, a thing is what it is (a conversation becomes an illustration about godly speech; a conflict between fellow workers becomes an illustration about reconciling enemies). We commonly call the literal use an example.

I could use the story of the building demolition figuratively. In this case, the point of the illustration would not be to give advice to banquet halls; rather, the restaurant sign becomes a symbol. The words on the marquee could resemble the mission statements of ministries that live on in their workers' hearts even after the organizations dissolve.

But I could also use the story literally, as wisdom for leaders, pointing out that as the owner finished closing down the building, she decided some things weren't worth doing. I might say: "It really didn't make any difference whether someone took the letters off the marquee. In your work, you have to make the same kind of decisions. What are you doing that does not need to be done?"

If you can't illustrate from an interesting experience one way, try the other.

Metaphorical Ability

As the previous point emphasizes, all illustrations are not metaphorical, but Jesus himself shows that metaphors can play a powerful role in preaching. Developing them is worth our time.

Most daily-life illustrations are ordinary, but infused with unique power to lift heavy sermon loads.

Metaphors compare two different things with one or more similarities. Through their differences and similarities, the one reveals something about the other.

When I look for metaphor in a slice of life, I begin by noting the feelings and connotations suggested by it, because that contributes to how metaphors give insight (again, it is both the similarities and the differences that make metaphors valuable). For example, if I call a big football player a tank, the metaphor gives understanding because it implies more than big. Lots of things are big—giraffes, buildings, puffy cumulus clouds, waterfalls—but they obviously don't suggest the same thing. Tank has associations of invincible movement, destructiveness, and unstoppableness.

Next, I break down my slice of life into its parts. To know what this thing is like, I first must know what this is. So I describe its nature and characteristics, especially its dominant, defining characteristic. Then I ask myself what it resembles.

For example, my small backyard has a power line running along the back of our property, about 10 feet off the ground. Connected to it is a power line that stretches over our yard to the house so that the two wires make a T. On one occasion, I noticed that the line stretching to our house bounced for seemingly no reason; neither birds nor squirrels had landed on it, and no wind was blowing. This piqued my curiosity. First, I noted how the bouncing power line connected to the perpendicular power line at the back of our property. Then I scanned that line from one end to the other. Sure enough, 10 yards from where the two wires joined at the T, a squirrel was walking the tightrope.

My illustration antennae sensed something, and I began considering how this could serve as a metaphor. I started with feelings. The image had mixed connotations: power lines are more or less unsightly, and squirrels can be looked on either as cute or as pests. Then I broke down what I saw: (a) an action with no immediately visible cause; (b) a connection; (c) a second related part; (d) a distant, indirect cause.

I realized the bouncing power line could serve as a metaphor of cause and effect, where the cause is not immediately apparent. This metaphor could illuminate the common situation of trying to solve a problem. Suppose a man and woman have an intelligent son who flunks classes in school. The teachers can't explain it. Neither incentives nor discipline have solved it. What the parents may need to do is "follow the power line," look for connections to other factors in their son's life not directly related to school work. Perhaps he is depressed that his mother had to resume working full-time and no longer has as much time to spend together. Or the "squirrel" may be a bully mistreating him in gym class.

Again, the key mental skill for finding metaphors is breaking down an experience to its distinctive parts, then using the pyramid of abstraction on them.

Vision

I have saved till last what may be the most important ability for gathering moving illustrations from everyday life, and that is vision. Vision sees what those lacking eyes miss. A person with inspirational vision sees uplifting things others are blind to. A person with a vision for joy or beauty, hope or purity, love or the glory of God sees these things where others do not.

For example, I have heard stories told in a way that evokes tender sympathy for a person. The preacher saw details in the subject's dress, speech, action, or facial expressions that signaled hardship and courage. He noticed these details because he had a sympathetic heart, and he communicated these details sympathetically.

We see with our heart. Whatever is in our heart, we look for around us and resonate with. A cynical person picks up constantly on the worst in those around him, while a hopeful person sees promise in a convict.

I was thinking about this principle as I sat in the park on a blistering summer Saturday, and I decided to experiment. I began to meditate on something positive and then intentionally looked for inspiring illustrations around me. I noticed an elderly woman on a walk. The heat index was well over 100 degrees, and she was using a walker. She passed under the shade of a small tree, stopped, slowly turned around, and sat on a little seat on the walker. To my surprise, after maybe three minutes she stood up, slowly turned around again, and then resumed her walk at a quick pace.

I thought: Now, there is a woman who hasn't given up. She's exercising, overcoming heat and hardship in conditions that younger people—me included—aren't anxious to exercise in. What fortitude.

I don't think I would have seen this illustration if my heart had not been tuned in to inspiration. As hot as I was feeling, I would have simply thought, That woman is going to kill herself.

Closely related to vision is imagination. Through imagination we see something in a different perspective, as I did when I saw the robin hunting worms as a vicious killer rather than a sweet harbinger of spring. Through imagination we see more than is there, or even what is not there. Imagination is an essential skill for developing metaphors, humor, and the stories used in fictional parables.

For example, in Dangers, Toils & Snares, John Ortberg writes:

When we take our children to the shrine of the Golden Arches, they always lust for the meal that comes with a cheap little prize, a combination christened, in a moment of marketing genius, the Happy Meal. You're not just buying fries, McNuggets, and a dinosaur stamp; you're buying happiness. Their advertisements have convinced my children they have a little McDonald-shaped vacuum in their souls: "Our hearts are restless till they find their rest in a Happy Meal."

I try to buy off the kids sometimes. I tell them to order only the food and I'll give them a quarter to buy a little toy on their own. But the cry goes up, "I want a Happy Meal." All over the restaurant, people crane their necks to look at the tight-fisted, penny-pinching cheapskate of a parent who would deny a child the meal of great joy.

The problem with the Happy Meal is that the happy wears off, and they need a new fix. No child discovers lasting happiness in just one: "Remember that Happy Meal? What great joy I found there!"

Happy Meals bring happiness only to McDonald's. You ever wonder why Ronald McDonald wears that grin? Twenty billion Happy Meals, that's why.

When you get older, you don't get any smarter; your happy meals just get more expensive.

Imagination comes from imagining, from creating, like children at play. The older we get, we may allow this faculty to atrophy because we play less and because imagination can certainly be abused in persuasion and storytelling (the word for imagination gone wrong is lying). But there is a great difference between lying and fiction, as well as the creative figures of speech used in literature. So imagination has a place, and it can be reawakened by the simple decision to imagine.

Listen to Max and John, and you will notice their vision and imagination.

Strength Under Control

To build muscle and gain a sense of how much illustration material surrounds you, try this exercise. Take a seat in your office or backyard, look around, and find an illustration angle for everything in your field of vision by intentionally using each principle from this article. With exercises like this, you'll find that the more you use these abilities the better you become at illustrating.

I hope you become an inspirational illustrator on par with John and Max. I also hope that your illustrations shed light on the Word, as theirs do, for great illustrators must resist one temptation. We can become so enamored with our illustrations that, in effect, they become the texts of our sermons. We can preach our illustrations rather than the Bible. Biblical preachers, on the other hand, ensure that their illustrations serve in a support role to the ideas that come from the biblical text. Often that means holding back a stellar illustration for another message.

Speaking of holding back, I conclude with one of my recent favorite slice-of-life illustrations that I have not yet been able to use in a sermon—but perhaps you can:

After several months of pain in one joint of my right thumb, I went to a hand specialist. I did not remember injuring the thumb, and I didn't want it to get worse. When the doctor came in to examine my hand, a nurse accompanied him. He sat down, greeted me, and got right to work. He looked closely at my hand, said, "Atrophy," and then said, "No." The nurse wrote on her clipboard. He named something else—an acronym like CLJ—then again said, "No," and the nurse wrote on her clipboard.

At that moment I realized he was proceeding through a checklist of possible problems with my hand. As he named the next item on the checklist, I found myself hoping, wishing, that he would again say no.

I want my thumb to be free from pain and strong all the days of my life. In the months prior to this appointment, I had begun curtailing my use of the thumb to see if that would bring it back to normal. When typing on the keyboard, for example, I started using my left thumb to hit the space bar instead of my right, thinking that perhaps that had brought on repetitive motion injury. I had to be careful how I turned the key in the car ignition. I had stopped shaking hands with my right hand. I was careful not to open bottles with my right hand. On and on.

And so it was that when the doctor again said, "No," I felt a quick sense of relief. He named another item on the checklist. I again hoped and longed for him to say no.

"No," he said. The nurse wrote on her clipboard. And so it went for some seven items. For each item on his list, he found nothing wrong, and so he finally sent me for X-rays. Minutes later, the doctor showed me the black-and-white images and said, "Here is the problem." Apparently, the ligament on one side of my joint had stretched, and the thumb had gotten out of alignment. He went on to describe treatments and to imply that this may never get better. The nurse wrote on her clipboard. This was not what I wanted to hear.

As I thought later about this experience in the doctor's office, I couldn't get over the visceral yearning I had, as the doctor went through his checklist, to hear him find no fault in my hand.

If that is so regarding my hand, which I will be using for a limited number of years on Earth, how much more when I stand before the One who judges my soul?

Like this unspectacular visit to the doctor, most daily-life illustrations are ordinary, but infused with unique power to lift heavy sermon loads. They are worth the effort to find them.

Craig Brian Larson is the pastor of Lake Shore Church in Chicago and author and editor of numerous books, including The Art and Craft of Biblical Preaching (Zondervan). He blogs on Knowing God and His Ways at craigbrianlarson.com.