Skill Builders

Article

Make Space in Your Preaching for Space

“Proxemics” is the study of the way humans use space. Coined by anthropologist Edward T. Hall in the 1960s, the term appears most often in the fields of intercultural and interpersonal communication. I’ll apply the concept to preaching below, but first let me explain and illustrate it.

The ‘Hidden Dimension’ of Communication

Hall called proxemics the “hidden dimension” of communication because the cultural rules regarding space are subconscious; however, they also tend to be rigid. Filipinos can be perfectly comfortable crammed into a jeepney with strangers, shoulder to shoulder and thigh to thigh, but an American on the same jeepney might twitch, shift, and corkscrew to carve out some personal space. Conversely, Filipinos might be uncomfortable with public displays of affection, but Americans might not think twice about holding hands, hugging, or even kissing in a public park.

Proxemics seems to be processed in the amygdala, the part of the brain associated with memory and emotion. We form impressions about people based on how they use space, especially when they violate cultural norms.

Perhaps you have experienced this—the British preacher who came to your church might have seemed stand-offish. Maybe you formed this subconscious conclusion based on their eye contact, body alignment, and distance in conversation. Or as you talk with the visitors from Brazil you may feel that they are chasing you around the fellowship hall. Your amygdala sends out sparks of discomfort so you back-up, but they keep advancing.

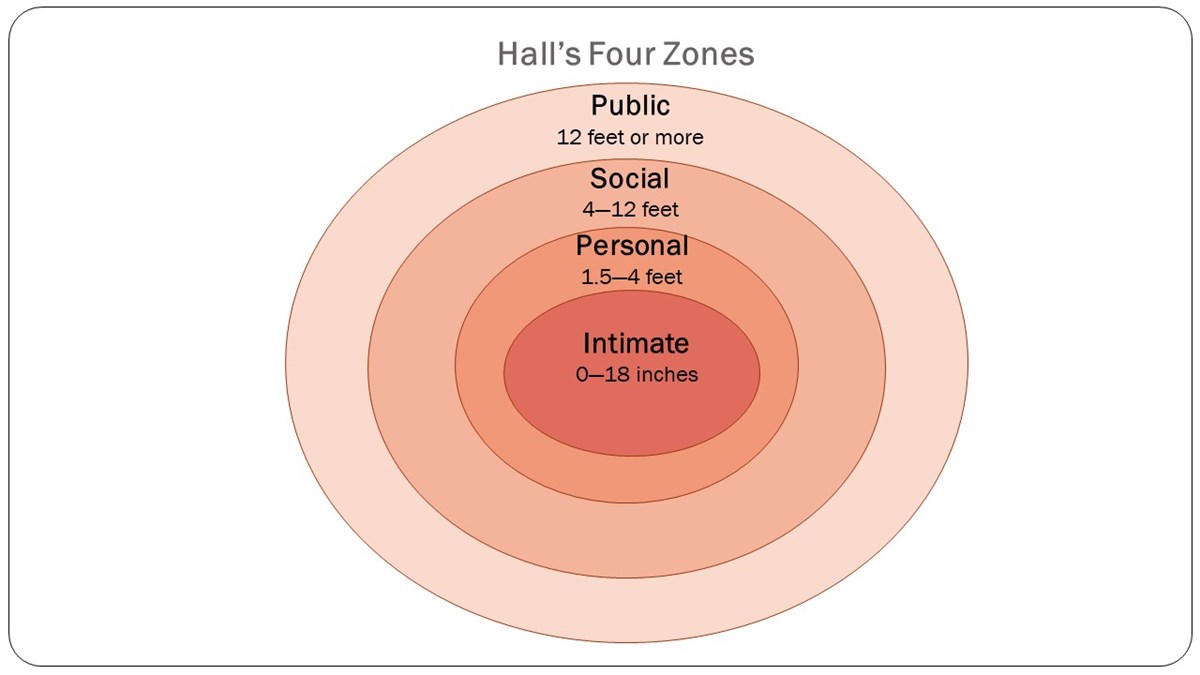

Hall categorized four proxemics “zones”: intimate, personal, social, and public. Each zone has a range because they vary from culture to culture.

Proxemics and Preaching

Awareness of proxemics can help us in many ministry settings such as small groups, counseling, and committee meetings. It can also make our preaching and teaching more effective.

Consider your use of the pulpit. What messages are embedded in the size of the pulpit and where it is in relation to the listeners? I cannot lay down iron-clad rules regarding the use of a pulpit because communication, including our use of space, is contextual. But I do urge intentionality. If you want a formal tone to your preaching, an imposing pulpit will help you achieve it. If you want an informal tone, you might use a small lectern with a stool nearby.

Theology is conveyed in choices like this, as the Protestant Reformers knew when they replaced the altar with the pulpit as the focal point of the church. So, what is your theology of preaching and pastoral ministry? How might you use proxemics to convey that theology?

The silent language of proxemics is culturally determined, but some uses of space are nearly universal. One of these is vertical space. In nearly every culture, when one person is physically higher than another, he or she is perceived as “top dog.” The nonverbal message about authority is plain when a preacher stands in an elevated pulpit.

I felt this keenly when I preached in the Anglican cathedral in Melbourne, Australia. To enter the pulpit you have to walk through a small door behind the ornate and elevated platform, and then climb a winding staircase. Upturned faces from listeners who are literally at the preacher’s feet sends a strong message.

The same is true for the preacher who speaks from “ground level.” In the early church, following the practice of the synagogue, preachers sat when speaking, perhaps in a large chair on a low platform. Notice that Jesus sat as he delivered the Sermon on the Mount (Matt 5:1). The setting was “on the mountain,” so it is likely that he positioned himself physically above the people so that they could see him, but perhaps also to convey a theological message about his authority.

In “public space,” the outside sector of Hall’s four zones, eye contact is essential. It compensates for the subtle messages easily conveyed in the other zones. Through the eyes, we send messages about the nature of the relationship (friendly, romantic, subordinate, etc.), the character of the speaker (sincere, trustworthy, dodgy, etc.), and the emotions that accompany the words (happy, sad, angry, etc.).

Because the eyes are the windows of the soul, I advise preachers to use only limited notes. In most American cultures, looking down at a manuscript often sends these messages: academic (concerned with precision), insecure (hesitant to reveal one’s heart), and preoccupied (focusing more on content—every jot and tittle of utterance—than on rapport).

The way we use space within the congregation also deserves intentional thought. Consider the messages that might be inferred when pews are arranged in perfect symmetry, when chairs are set up in a semi-circle, or when the Gospels are read from the midst of the congregation as in liturgical traditions.

In your church, do people stand when the Word is read? How close to each other do they sit? How might you use proxemics to promote unity and generate the natural energy that comes from physical proximity?

There are few, if any, rules of proxemics, except perhaps this one: be intentional. Make space in your preaching for space.

Jeffrey Arthur is professor of preaching and communication at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.