Skill Builders

Article

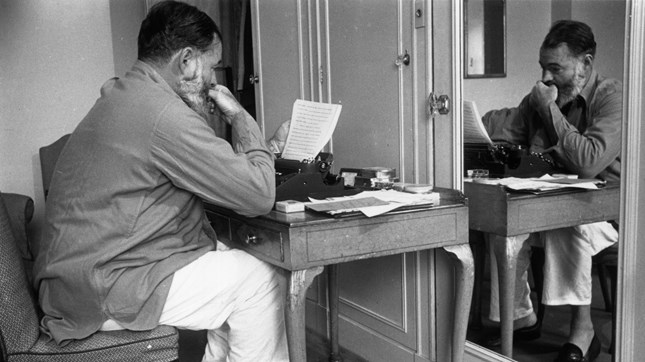

What Preachers Can Learn from Ernest Hemingway

The list of what preachers should not learn from America’s most iconic 20th century writer, Ernest Hemingway (1899-1961), is depressingly long. You will want to stay far away from his multiple divorces, insatiable appetite for alcohol, and his brawling nature, for starters. Still, when someone as notable as Ken Burns turns his filmmaker’s eye toward you, chances are strong that you (like baseball, jazz, and the Civil War) are a subject worth examining. In Hemingway’s case, his virtuosity as a writer has so much to teach preachers looking to enhance their craft.

If you are new to this series, my thesis is that preachers are, among other things, writers, and we have much humble learning to do at the feet of those who paint with words, whether they be songwriters, sportswriters, speechwriters, or in the case of Hemingway, a master of the novel, short story, and journalism.

In their three-part documentary on Hemingway, Ken Burns and Lynn Novick lay out Hemingway’s raucous life in three phases.

- In “A Writer” (1899-1929), we see this Midwest physician’s son apprentice in journalism at the Kansas City Star, nearly die in World War I while serving as an ambulance driver, gain literary notice with short stories, and produce his first truly great novel, A Farewell to Arms.

- In “The Avatar” (1929-44), Hemingway struggles, in Tobias Wolff’s memorable phrasing, with becoming an “avatar” of himself and struggling with the public image he has created (a phenomenon that preachers often experience on a smaller scale). In this season of his life, Hemingway writes non-fiction about Spanish bullfighting and African hunting. Africa, in fact, provides the setting for two of his best known short stories, “The Snows of Kilimanjaro” and “The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber.” He also pens his novel of the Spanish Civil War, For Whom the Bell Tolls.

- In the final episode, “The Blank Page” (1944-1961), Hemingway’s accumulating injuries, marital difficulties, and excessive drinking war against his writing. Still, his long tenure in fishing villages in Key West and Cuba lead to my personal favorite of his novels—The Old Man and the Sea. Extensive stays in a psychiatric hospital fail to conquer his increasing paranoia and depression, leading tragically to Ernest’s death by suicide.

My purpose here is to share a few themes from Hemingway’s life and art that are particularly useful for those who turn words, not into novels, but into sermons, week after week.

‘Grace under Pressure’: Fighting the Fear that Wars Against Your Preaching (and Living)

In July 1918, when he was still in his teens, Hemingway drove an ambulance for the Red Cross during World War I. While stopping to pass out chocolate to infantrymen, he was hit by an enemy mortar shell, taking in over two hundred shards of shrapnel and suffering the first of many debilitating concussions over the course of his life. He feared at the moment that he might die, later claiming that he felt his soul coming out of his body like “a silk handkerchief.” Scholars have speculated that this early terror and flirtation with death set a major theme for his writing life.

In The Short Happy Life of Francis Macomber, Francis’ wife Margot is openly having an affair with their safari guide Robert. Their affair seems to have been ignited by the cowardice Francis demonstrated while running scared when a lion charged him. In his own words, Francis “bolted like a rabbit,” leaving Robert to kill off the wounded animal. Francis is haunted by Margot’s adultery and his own cowardice. Later, when hunting three buffalo, Francis steadies himself and fires straight at the charging bull, only to be shot from the back by Margot (accidentally or on purpose—we are not told). A short life, yes, and a tragic one. Still, as Francis faces down the charging bull, he seems to gain back the manhood he had previously lost.

Like Francis, we cannot control so many things of life's threats which charge toward us. What we can do is pray for the courage to face each fear faithfully.

In a letter to F. Scott Fitzgerald, when speaking of the bullfighting he was spending so much time observing, Hemingway used the elegant phrase, “grace under pressure.” While there is some dispute about exactly what he meant by it, that phrase resonates for preachers, like me. It is a long way from the wide-open jungles of Africa to the shelter of the air-conditioned sanctuary. Still, the life of a preacher has its own pressures and opportunities for steely-eyed grace.

You could think of a homiletical “grace under pressure” along several planes. First, there is courage in the selection of the sins we expose and the sins we ignore. Will we use our pulpits to prop up the dominant cultural biases of our church’s power base? Will we dish out the kind of homiletic “red meat” which fires up our constituents but fails to acknowledge our blind spots? Sometimes, it is easy to point out the foibles of those sections of society that our congregation easily scorns. It takes courage to confront the congregational logs in our own eyes.

A second type of courage dares us to preach “experimentally,” if you will. Any decent religious wordsmith can deliver a fine sounding speech. Too often, that’s what the weekly sermon becomes for the veteran preacher—a product from a speaker’s workshop rather than a cry from an impassioned soul. It takes courage to allow the text in the study to get deep inside our lives. Will we live experimentally and autobiographically with the Scripture’s implications? Will we risk being chafed by its rough edges? Will we, on some level, “try out” the application before we readily scoop it out onto the plates of our hearers?

A third type of courage places our own preaching process in the center of the scope. Take a moment to answer this question honestly. Write down the first thing that comes to your mind when I ask: What is the most under-developed part of your preaching?

- Is it the exegesis—are you careless when it comes to excavating the necessary historical and interpretive details of the text?

- Is it illustrating—do you default too quickly to overused stories of your children (or grandchildren)?

- Mine is application. Way too often, I stop short of answering the “what must I do to be saved” question that is on the minds of attentive listeners.

It is easy for preachers to, in tennis-speak, “run around our backhands” and double down on our strengths. What if this Sunday we look the charging bull in the eye and refuse to run away?

‘The Dignity of the Iceberg’: Pursuing Simplicity to Create Profundity

I remember reading, years ago, a brilliant prose stylist, Joan Didion, praising the first paragraph to A Farewell to Arms, it begins: “In the late summer of that year we lived in a house in a village that looked across the river and the plain to the mountains.” What stood out to Didion? Certainly the rhythm of the words—what she called their “liturgical cadence.” Perhaps even more the simplicity of the language—of the 126 words in the paragraph, only one has as many as three syllables, and 103 have only one syllable.

Neal Plantinga once stated that the best of children’s literature is written with a “noble simplicity.” Simplicity, of language and ideas, is often the missing piece of our preaching. Sometimes intentionally. Have you ever heard a preacher speak of a “Christocentric worldview” when perhaps “the mind of Christ” might have connected with more listeners? Have you ever been tempted to impress the most theologically learned of your listeners with phrases that mystify the majority of the congregation (e.g., “as Bavinck has so aptly put it in volume three of his Dogmatics …”)?

Often, we preachers want to get a good return of investment on the minutes or hours we’ve spent reading exegetical materials. We cannot bear to leave out those tasty Bible facts we took the time to uncover. As a result, our sermons start to feel like those suitcases which we sit upon but never quite seem to close.

In Death in the Afternoon, Hemingway explained a key principle to his prose writing:

If a writer of prose knows enough about what he is writing about he may omit things that he knows and the reader, if the writer is writing truly enough, will have a feeling of those things as strongly as though the writer had stated them. The dignity of movement of the iceberg is due to only one-eighth of it being above water.

There is something here for the preacher. We usually know far more about a given text than we have time to say. It kills us to throw away the juicy tidbit of rabbinic interpretation, the scholar's debate about textual inconsistencies, the darling story of what our two-year old did to Chuckie at Chuckie Cheese's. We are inherently limited by the 20-40 minutes we have each Sunday to preach. All of that reading is helpful, and some of it directly informs our approach to the sermon. Still, too many scattered details detract from the central thrust of the sermon.

What wrecks our sermons more often, however, is a complex or even confusing flow or structure. I’ve written before about a weekly sermon meeting our staff has held for over a dozen years. The person preaching that Sunday (usually me) brings a rough draft and reads it rapidly while some staff members listen and give feedback to strengthen the sermon.

In our early experiments with these meetings, I would nervously read through my draft, often hearing how disjointed and unfocused the sermon sounded as it was coming out of my mouth. Sometimes, my friend DJ would say something like this, "Larry, do me a favor. Put down your notes and tell me what you think this sermon is really about.” Sometimes angrily, defensively, I would blurt out the essence of the sermon, off the cuff. Invariably, DJ would look me in the eye and say, “Say that!”

What we need is what Hemingway himself discovered in Paris. In A Moveable Feast, he described what helped him out of the writer's block that would inevitably thwart him: “I would stand and look out over the roofs of Paris and think, 'Do not worry. You have always written before and you will write now. All you have to do is write one true sentence. Write the truest sentence that you know.’”

Powerful preaching leans upon our willingness to prayerfully work and wait for that central, potent, truest theme we find.

‘First You Must Live It’: Living Adventurously to Preach Imaginatively

I am going to guess if we are like most full-time preachers, our life cycles from church office to home to sanctuary and back again. Unlike Hemingway, there’s a better than average chance that you’ve never fished for marlin in Key West or nursed an espresso at a cafe in Paris. Still, I wonder if there is something in Hemingway’s adventurous life that calls out to us as preachers?

There is a quote, attributed to Hemingway, which states, “In order to write about life, first you must live it.” We might, for our purposes, amend this to say: “In order to preach imaginatively about the full range of life, we must first live it.” Some of the best sermons emerge, not from breathing the musty print of old commentaries (as important as this is!), but tracking the sounds and sights of a T-Ball dugout, a hospital waiting room, an old-growth forest, a rehearsal dinner, or a historical museum.

A preacher’s willingness to “travel” (even if it is across town) and to engage the new and the old and the painful and joyful, opens up a fresh exposure to image, insights, stories, and perspectives.

What might a commitment to live a little more adventurously look like for you? As preachers, our lives and stations of life and budgets vary greatly. Still, here are some ideas to consider:

‘Exotic’ Conversations

We talk most with people who occupy our cultural landscape. Conversations that cross borders can open up vital new pathways in our imagination. Ask a teenager what they are most looking forward to this summer. Ask a person of another race what people often misunderstand about them. Ask a healthcare worker, a nanny, an attorney, and a produce manager about the hidden pains and joys of their jobs. Ask an atheist if they ever had any kind of belief in God, and if so, when and how things shifted.

I think you will discover that these conversations are portals into worlds that many of your listeners inhabit. Hemingway was a master at this. In the documentary, the Irish novelist Edna O’Brien says that there are parts of A Farewell to Arms that seem like they could have been written by a woman (a statement she meant as a compliment, although she was not sure Hemingway would take it that way!). We serve our listeners best when our preaching engages a wide variety of points of view.

Mission Trips

By “mission trip,” let’s include excursions that not only extend across oceans or state lines but also across town. Just as Hemingway’s adventures at war, on a boat, or at a bullfight expanded his literary horizons, something similarly powerful happens when we venture out of our own neighborhoods, especially with a mind to serve others and share the gospel.

Beyond modeling this for our congregation, our adventures serving in different countries and cultures widens our understanding of the gospel. We often find people who have suffered greatly, and in the process have proved true Hemingway’s maxim about pain: “The world breaks everyone, and afterwards many are strong in the broken places.”

One of my first global mission trips was in a terribly poor section of Lima, Peru. I actually left on the trip during the latter part of a sermon series on the Book of Jonah. I preached Jonah 3 and then got on a plane, and in Peru I not only reflected upon Jonah 4, I lived it.

Do you remember how Jonah’s miraculous vine, the one that temporarily provided him shade, was destroyed by a worm? Jonah’s selfishness to his loss of comfort was measured against God’s concern for the welfare of Ninevah. In Peru, I experienced the loss of the normal “shade” I was used to, shade that sheltered me from the challenges so many parts of the developing world regularly face. Without central heat and air, comfortable transportation, hot showers, easily obtained and safe drinking water, Western restrooms, cellphone, television, or my favorite Tex Mex, or Starbucks, I realized I had a choice. I could, like Jonah, become angry and depressed, or I could see the world beyond my shade tree of relative affluence. I could marvel at these joyful, poor Peruvian Christians, strong in the broken places of their painful lives.

When I finally got back to my home church, I was able to preach Jonah 4 with a passion and empathy which would have been unimaginable without the blessing of that trip to a different hemisphere from my own.

Conclusion

“If a writer stops observing he is finished,” Hemingway stated to George Plimpton, editor of the Paris Review. We could wish that Hemingway had observed deeper truths about the source of his sorrows and God's promised mercy. Still, his maxim fits preachers equally as well: “If a preacher stops observing they are finished.” The literary world can give thanks for Hemingway's courage to observe the world at war and at play and to render it with beauty and clarity. May we courageously open our eyes as well—to the depths of Scripture, the depths of the Spirit, the depths of our hearts, and the wideness of the mercy God has spread everywhere.

Larry Parsley is the senior pastor of Valley Ranch Baptist Church in Dallas, Texas. He is the author of An Easy Stroll Through a Short Gospel: Meditations on Mark (Mockingbird Ministries, 2018).