Skill Builders

Article

Stirring Memory

In a previous article for Preaching Today, "Preaching as Reminding," I presented a biblical theology of memory by tracing that theme through Deuteronomy, the Prophets, and the Epistles. We saw that the stirring of memory is a legitimate function of preaching. Sermons do not always have to teach new things or change people's minds. Sometimes they can simply repeat truths already known and believed, especially when preaching to people in the covenant. Auditors who stand on Mars Hill need explanation and persuasion, but auditors who stand on Mt. Gerazim need reminders. Of course, telling people what they already know and believe runs the risk of boring them, but effective stirring of the memory refreshes affect and belief. It is much more than simple psychological recall.

Activities stirred memory performs

Here are some of the "activities of will or body" that a stirred memory performs. It can:

- Solidify faith, so that we can stand and not fall away. (1 Cor. 15:1-2; Hebrews 2:1, 5:11-12)

- Prompt thankfulness, as we count our blessings naming them one by one. (Ps. 105:1-5)

- Give comfort in trials. (Ps. 42:5-6; 77:7-20)

- Work repentance, for we cannot mourn what we have forgotten. (Matt. 26:75)

- Raise hope. We find strength for today and bright hope for tomorrow as we remember the faithfulness of God in the past. (Psalm 71:12-16)

- Walk wisely. Wisdom is the application of previously learned knowledge to current decisions. When the devil puts truth on trial, knowledge must be called to the witness stand. (Prov. 3:1-2, 4:5-6)

- Avoid sin. (Ps. 119:11).

- Form identity. (Isa. 46:5-11; Jer. 51:50; Ezek. 16:22) Old Testament scholar Walter Brueggemann comments that when children of the covenant are in exile, their present reality can seem to be the only reality. They forget their God-given identity as Babylon squeezes them into its mold: "When we have completely forgotten our past, we will absolutize the present and we will be like contented cows in Bashan who want nothing more than the best of today…. It takes a powerful articulation of memory to maintain a sense of identity in the midst of exile."

- Subvert the status quo. Brueggemann again:

The empire, Babylonian or any other, wants to establish itself as absolute, wants the present arrangement to appear eternal in the past as in the future, so that after a while, one cannot remember when it was different from this, which means having available to our imagination no real alternative. Against such imperial absoluteness and positivism, memory can be a keenly subversive activity.

4 techniques of vividness

So, how can preachers stir memory? A bland and bald recital of truth, like the droning of a schoolboy saying his lesson, will not stir. Rather, we take the assertion of Jonathan Edwards as our goal:

God hath appointed a particular and lively application of his Word to men in the preaching of it, as a fit means … to stir up the minds of the saints, and quicken their affections, by often bringing the great things of religion to their remembrance, and setting them before them in their proper colors, though they know them, and have been fully instructed in them already.

How we can bring the great things of religion to remembrance so that the old, old story is heard again with power? The answer I provide takes us into the realm of rhetoric, particularly to the canon of style. An indivisible relationship exists between what is said and how it is said. Aristotle put it this way: "It is not enough to know what we ought to say; we must also say it as we ought." Specifically, I'd like to suggest that four techniques of vividness—the use of concrete and imaginative language delivered well—can help us stir memory.

Association

One way to re-animate a dormant idea is by analogy. Preachers can tap into listeners' previous sensory experience, with its attendant power of holding attention and rousing emotion, and transfer that power to the dormant idea. For example, let's say that you are preaching from the Good Samaritan and you proclaim this biblical truth: "God calls Christians to love their neighbors." That idea has been pulled from the closet so often that it is threadbare. So you need a vivid image that will compel involuntary attention, comprehension, and assent. "God calls Christians to love their neighbors, as Mother Theresa loved the people of her neighborhood." If the congregation has direct experience of Mother Theresa (unlikely) or secondhand experience of Mother Theresa through books, videos, interviews, etc. (likely) then the tired idea gains some traction by virtue of the association. That traction would be even more powerful by extending the vivid language—tell a story of Mother Theresa, show a picture, or quote her. "God calls Christians to love … like Mother Theresa. Let me tell you about a trip I took to India where I actually met Mother Theresa … ."

Even better than an example about Mother Theresa would be an example of someone from the listeners' direct experience, perhaps Deacon Smith whom they all know and love. "God calls Christians to love … like Deacon Smith. When I first moved to this area, eight years ago, I didn't know Deacon Smith and he didn't know me, but he showed up on my front porch, helped me move furniture … ."

Associations can also be figurative: "God's love is protective like the Smiths' dog that jealously guards her newborn puppies." If the listeners have direct experience with the Smith's dog (maybe you are speaking to the youth group which is meeting at the Smith's house) the analogy can be short. One line will suffice because the young people just tried to pet the puppies, and the mother dog growled protectively. If the listeners do not have that kind of direct experience, the analogy will need to be longer. Paint a picture; tell a story.

Spurgeon was a master of analogy. Notice how he presents this potentially bland idea: "Give your very best to your Lord." He frontloads images and saves that sentence for last:

If you were making a present to a prince, you would not find Him a lame horse to ride upon; you would not offer Him a book out of which leaves had been torn, nor carry Him a timepiece whose wheels were broken. No, the best of the best you would give to one whom you honored and loved. Give your very best to your Lord.

Self-disclosure

Self-disclosure is a special kind of "association" that links the message with direct sensory apprehension of the messenger. That is, through the senses of sight and sound—what the speaker looks like and sounds like—listeners associate a potentially abstract proposition ("Christians should love one another") with a flesh and blood person. If the proposition has lain dormant in the hearts of listeners, it now commands their attention because, in the person of its advocate, it says "look me in the eye."

C. S. Lewis discovered this as he was working out his apologetic method during WW2. He found that people could not receive the good news of the gospel because they had little sense of the bad news of their sin. Then he discovered how self-disclosure can "awaken the sense of sin." Therefore, he recommended self-disclosure to other apologists: "I cannot offer you a water-tight technique for awakening the sense of sin. I can only say that, in my experience, if one begins from the sin that has been one's own chief problem during the last week, one is very often surprised at the way this shaft goes home." Notice that Lewis assumes that a "sense of sin" already exists, but it slumbers. His job was to awaken it by stirring memory. That stirring occurred when listeners associated with the speaker's self-disclosure.

Dramatization

This technique is a type of support material that depicts an abstract idea in the form of characters in a drama. When done well it animates slumbering knowledge. Haddon Robinson uses it in a sermon from Matthew 25 with the repeated phrase, "Whatever you did for the least of these, you did for me." I heard Haddon preach this in chapel at Gordon-Conwell. All of the students knew that verse, and I suppose that some of them had even preached it, so Haddon's job was not to teach a new truth, but rather to vivify an old truth. Here is a close paraphrase:

Since it's the judgment of the nations, I imagine I'll be there. I'll be standing before the King and he'll say, "Robinson, did you bring your datebook? Look up Oct. 27, 28, 29, 1983."

"Oh yes, Lord. That's when I was made president of the Evangelical Theological Society. We had a big meeting down in Dallas. I lived up in Denver. I wrote a paper: 'The Relationship of Hermeneutics to Homiletics.'"

And the King will say, "Well, I don't know anything about that. I don't go to many of those meetings. No, what I had in mind happened before you went down to Dallas. There was a couple on the campus. I allowed them to have a twenty-five day check in a thirty-one day month. Bonnie told you about them. And you folks put some money in an envelope and put it in their box. Remember that?"

"Boy, that was so long ago. Bonnie would probably remember it better than I would."

The King will say, "I remember it. You put that money in that box and gave it to me. I've never forgotten it. Look at the first week in March, 1994."

"Oh yes, Lord, that's when I was mentioned in Newsweek magazine as one of the best religious communicators in the English-speaking world!"

"Well, I don't read those magazines much. They're so inaccurate. And that story shows how inaccurate they are! No, I was thinking of when you were teaching on that day. You were leaving class to go to a meeting, and there was a young woman sitting there. And you said, 'How are you doing?' and she began to weep. You sat down and she told you that her brother had passed away a couple of days ago and her father a couple of months ago. She found the burden of that grief so heavy that she didn't know if she could bear it. And you didn't know what to say, so you just listened. Remember that?"

"Yeah, I guess I do. I felt so inadequate."

And the King will say, "When you stopped to listen to that woman, you were listening to me, and I have never forgotten it."

There are going to be a lot of surprises at the judgment. You know all that stuff you put on your resume. It won't matter much. What will matter will be acts of kindness and compassion.

Closely related to the technique of dramatization is "apostrophe" where the speaker addresses an imaginary figure, even an inanimate figure, as when the Apostle Paul exclaims, "O death, where is your victory? O death, where is your sting?" An extended apostrophe might sound like this:

Stand up straight, Mammon, I'm talking to you. Look me in the eye. What makes you think you can tell me what to do? Who put you in charge? You may rule in downtown Singapore, but you do not rule in this church! We are in the world but not of the world. You may be in league with the prince of the power of the air, but we do not fear him or you. No one can serve two masters, so we renounce you, Mammon, and we announce our allegiance to the one and only King of kings.

If you hesitate to use so much imagination, realize that you will not likely use this technique very often. But when you do pull it from the homiletical quiver and send it from the string, it can pierce the heart. Be encouraged by the words of John Broadus:

Imagination does not create thought; but it organizes thought into forms as new as the equestrian statue of bronze is unlike the metallic ores when they lay in the mine … . Imagination is requisite if we are to conceive correctly and realize vividly the scriptural revelations concerning the unseen world and the eternal future. Faith believes these revelations, and imagination, aroused by faith and called into its service, makes the things unseen and eternal a definite reality to the mind, so that they affect the feelings almost like objects of sense, and become a power in our earthly life.

Embodiment

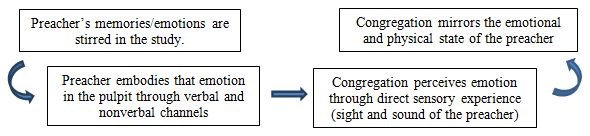

I use this term to refer to delivery, the emotion-generating power of the non-verbal channel. The congregation sees and hears an embodied message, and then tends to mirror the physical and emotional state of the preacher. Rhetorician and preacher Hugh Blair said, "There is an obvious contagion among the passions."

The "contagion" spreads like this:

Today this "contagion" is likely to be described in scientific terms as with studies of "mirror neurons"—special nerve cells of the brain that prompt us to imitate the muscle tone and behavior of the person speaking to us. Whatever reason for the "contagion," we know that it is indispensable to preaching. Dabney says that the "law of sympathy" is the preacher's "right arm in the work of persuasion."

Conclusion

The next time you need to re-animate half-dead, half-forgotten truths that feel trite (it will probably be this Sunday!) pay attention to your style. Associations, self-disclosure, dramatization, and delivery that embodies the truth are four ways we can stir memory.

Jeffrey Arthur is professor of preaching and communication at Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary.